Most Indian game developers either stick around in the industry, moving from one studio to the next or they exit it altogether to work on something totally unrelated to video games. Anand Ramachandran isn’t your average Indian game developer. Rather, he’s banking on his lifelong passion of video games and a career in games design honed at the likes of Zynga and Bharti SoftBank-backed Tiny Mogul Games (which was later folded into Hike messenger) to help education benefit from the interactivity of video games at his new start up Big Fat Phoenix.

However Ramachandran didn’t get his start in the games business. As a college drop out, he found himself working in digital media and advertising in Chennai during the first dot com boom at a time when multimedia CD ROMs were popular.

“We were interested in interactive design at that time,” he says. “We started figuring out tools like Flash and Macromedia Director for making CD ROMs. That time we realised this could be used to make games too. We were huge fans of point and click adventures. And we realised we could make something like that with these tools. This was before the point in time when Flash was prevalent for making games.”

Although this didn’t end up going anywhere. Reason being, the software wasn’t mature enough and the team didn’t have the skills to see their ideas through.

Nonetheless, the false start did little to quell Ramachandran’s passion for games. He eventually landed a gig as a columnist for New Indian Express following a chance meeting with then Editor-in-Chief Aditya Sinha at a cafe in Chennai.

“He asked if I would be interested in writing a column about games,” he says. “I told him I didn’t know about comics but would be delighted to write a column about games.”

He already had a blog at the time called Boss Fight which he’d use to pen his thoughts on video games. At the time, games were far from mainstream and he was one of the first critics at a mainline newspaper that helped legitimise it.

“I started writing about games long before I started making games,and from there I was generally around, attending the usual circuit of conferences like IGDA,” he says. “I always wore my love for games on my sleeve. It was a thing if you knew me, you knew that I was crazy about video games. That’s the only thing I would talk about to most people all the time.”

It’s this passion of games that led to his first break into the business courtesy his friend and filmmaker Prakash Kovelamudi. In 2006 Kovelamudi set up A Bellyful of Dreams Entertainment, a company to make movies as well as capitalise on their transmedia potential.

“He was trying to put a team together to put other media around films like comics and games and stuff and asked if I would be interested,” he says. “I was. So what I did was wrap up everything in Chennai at the time. This was the chance I’ve been waiting for and moved to Bombay.”

Making Once Upon a Warrior for mobile phones

A Bellyful of Dreams Entertainment’s first movie was a Telugu fantasy adventure Anaganaga O Dheerudu (Once Upon a Warrior) directed by Kovelamudi and was co-produced by Disney. As a part of deal there would be a feature phone game too.

“It was actually Disney’s first production in the South,” he says. “And that associated game was first thing I actually shipped.”

Though getting there wasn’t without its challenges. For starters, Ramachandran didn’t really know how to make or design a game then.

“We were clueless at the time on how to make games,” he says.”We only had intent but I was pretty clueless about how to make games. I was like, ‘how hard can it be?’”

Furthermore, the movie featured a blind protagonist that would be playable in the game as well. Translating this crucial aspect from the movie to an interactive medium that’s known for its focus on visuals would be a challenge. Thankfully, the solution was remarkably simple yet effective.

“We had an idea of a bubble around the character,” he says. “When the character stands still, the bubble gets wider because your senses are sharp, but when you’re running, jumping and stuff, the bubble gets significantly smaller, so you can’t see too much around the character. So it was sort of like a balance of staying still to be able to expand your perception, and then move around and beat things. It was a fairly regular platformer, plus this mechanic.”

Here’s what Ramachandran’s debut game looked like. You can’t play it easily nowadays due to the inherent nature of feature phone games.

With this core mechanic in play, Ramachandran likens the end result to Java-based Prince of Persia games for mobile handsets. While A Bellyful of Dreams handled design, a Pune-based studio, Xerces was charged with putting the entire game together.

“They were very experienced in building this,” he says. “We just had to explain the vision and documentation which I had some idea of how to present it. They were able to take it and translate it quite easily despite our shitty documentation.“

As for how the game performed, Ramachandran has no idea. This was after all, a title sent to carriers for users to download to their feature phones. At a time when smartphones were thought of as luxury goods and app stores from Apple and Google were still in their infancy, getting credible information on how a game sold was tough.

“I had no idea about data and analytics and stuff like that. We had no idea,” he says before hazarding a guess. “I don’t think it must have done very well, because the movie was very middling. It wasn’t a major hit. So in those days for a game to do, well, at least the movie has to make a huge splash, right? By those standards, it came out well, it was a game that I was actually happy to see and play. It was a fun game and the quality was good. How well did it do? I actually have no clue. My guess would it be nobody played it.”

How to get a game design job at Zynga without being a game designer

After this, Ramachandran found himself at Zynga India. He considers himself fortunate applying to the company when he did on the advice of a friend. The leadership of the studio at the time was willing to take risks in terms of hiring.

“You have to give it to Shaan [Kadavil], Steven [Lurie] and the people who built Zynga India,” he says. “They genuinely had vision on how to build a team without which I would never have gotten in. No college degree, no experience really making games, nothing to suddenly go to Zynga.

Zynga India realised they’re not going to get qualified game designers in India. They just looked for smart people with creative chops, who would come in and do it because Zynga had lot of international game designers to learn from.”

Ramachandran was the second designer hired at the time and along with colleague Anshumani Ruddra, built Zynga India’s design team from scratch.

“When I left there were about maybe 20 designers or so at Zynga India at the time,” he says. “It was the first place where I really learned how to make games. With Zynga it’s not really how to make games from the get go instead you start with how to make features for existing games.”

This is because it was cheaper for Zynga to continue supporting current games in India while its US division would work on newer titles.

What YoVille learned from Baldur’s Gate 2

The first feature Ramachandran worked on was for a now defunct Facebook game called FishVille. It had players managing a virtual aquarium, buying fish, feeding them, and dealing with other such minutiae.

“It’s a classic doll house Zynga game,” he says. His contribution to it involved reducing the tedium players had to feed each fish individually.

“Players were asking for a way to feed multiple fishes at a time so I came up with this robot multi-fish feeder, which would drop like five pellets of food at one click,” he says. “It’s just literally you click once and a bunch of them would be fed but the thing with features are that you got to make it look cool. You got to make it like look and sound pleasurable to use and stuff. It was a very good first feature to do because it made me focus on user experience rather than mechanical stuff.”

From there he moved on to working on Vampire Wars, a game similar to Zynga’s then popular Mafia Wars but with vampires as well as YoVille — a life simulation game akin to Animal Crossing that’s still playable today after original developer Big Viking Games bought it back from Zynga in 2014 and renamed to YoWorld.

YoVille ended up being extremely impactful to how Ramachandran approached game development.

“When I joined the YoVille team I was like ‘what is this game? I mean, what is this? There are no mechanics, there’s no challenge. There’s no, you know, there’s no compulsion!’”

He really didn’t understand the game at the time and felt there were ways to improve it, taking inspiration from RPGs of yore like Baldur’s Gate 2.

“I was like, ‘no, I’m going make this a better game and I’m going put in quests and I’m going put in storyline and I’m going put in progression. And we tried, we tried Yoville jobs, a feature where you could stat up with RPG trimmings as well as other features. All of them bombed one after the other. I was really frustrated. I felt I was trying to make the game better but people did not like it.”

Epiphany hit an upset Ramachandran days later while he was testing one of the game’s monthly themes. These were regular drops of content featuring new cosmetic gear for players to customise their spaces with like furniture, clothing lines, and pets.

“So there was this rain forest theme, and I got a rain forest tree house and I started decorating and suddenly I started having fun decorating it,” he says. “Before I knew it I was thinking about where I was putting chairs and rugs. My first impulse was to call my wife and my son to ask them to check it out. Then I realised wait, this is what this game is about. At that moment it clicked. This game is about decoration. This is about things looking cool. Not about mechanics.”

This resulted in Zynga India shipping a series of features that he describes as “all gangbusters”. Some of which are present in a host of major chat apps today.

“We shipped a feature in which you could have moods to your speech bubbles,” he says. “So if you’re angry the speech bubble will be fiery or if you’re saying something lovey dovey the speech bubble will be all hearts.”

This was followed up by emotes that let players dance or wave as well as multiplayer gestures allowing two players to hug, high five, or kiss.

“YoVille taught me that once you start listening to your player and empathising with your player and ship features which they care about, not what you want to build, you’re going to be successful,” he says.

Interestingly, all the games that Zynga India took over from the US team were those waning in popularity. Although Ramachandran never saw this as a deterrent.

“The people who remain are actually hardcore players who really love the game,” he says. “They would be very vocal about

whether they like or whether they dislike a new feature and listening to player voices came from them.”

Nonetheless, it would not be long before Zynga India and Ramachandran found themselves working on a game it could call its own.

How Zynga India shipped Zynga’s first game that wasn’t developed in the US

YoVille’s success afforded Zynga India new opportunities. It worked on an expansion to Hidden Chronicles, a hidden object game for Facebook, called Search for the Seven Sons which was well received. This was followed up by a brand new game called Hidden Shadows, it was the first title for Zynga to be shipped by a studio outside of the US. To call it a big deal would be an understatement.

Zynga San Francisco had a hidden object game that was going nowhere and on the verge of being cancelled. The India team volunteered to take it on and see it to completion. While doubts arose on their ability the then creative director of Zynga’s San Francisco studio Cara Ely vouched for them.

“Cara was backing us heavily because she wanted to see the game made,” he says. “She was convinced we had the chops to do it.”

In addition to this, its efforts on YoVille and Hidden Chronicles earned them the confidence of Zynga’s leadership.

“We had shown that we know how to make things from scratch and hence full credit to those leadership of Zynga India at the time. Zynga San Francisco to be fair decided that it’s worth taking that bet. Shaan [Kadavil], Steven [Lurie], and Deepthi [Menon], all those people really had the vision to push and fight for it. The leadership trusted us. Hence [Zynga] San Francisco trusted them.”

Thus Hidden Shadows was born. It was a hidden object game that had players diving into a supernatural crime story and allowed for cooperative play. It hit Facebook on June 27, 2013.

The timing could not have been worse. It released when Zynga was pivoting to mobile following changes to Facebook’s algorithm. A deluge of user complaints due to spammy notifications on Facebook from players to non-players asking for help coupled with a shift in Facebook’s own policies led some to opine the end was near for the company.

To make matters worse, Zynga’s own metrics for success were stacked against it. Hidden Shadows had about two million users by September 2013 according to one estimate.

“The game was really successful except by Zynga standards,” Ramachandran says. “In Zynga unless you get like 10 million DAU [daily active users], they’ll close down the game saying it’s a failure. So by Zynga standards, the game did poorly. But by any other standards, it actually did fairly well. And we really enjoyed making it, it was a fabulous experience.”

Nonetheless, Hidden Shadows for tablets was announced when the Facebook version shipped. It never saw the light of day partly due to a middling metrics as well as a crowded production pipeline.

“Zynga was trying to move to mobile and had a lot of games in production like FarmVille and Empires and Allies at the time,” he says. “We didn’t have the resources to do it simultaneously [with the Facebook launch] so there was supposed to be tablet launch later on. We had working builds but then the game got cancelled within six months or so of release. It wasn’t a priority. If the game had been successful we would have launched.”

Ramanchandran ended up moving on to Tiny Mogul Games, a Bharti Softbank venture. Though he was far from remorseful about his time at Zynga.

“Zynga gets a lot of flack and some of it deservedly so,” he says. “But you have to give it credit for at least Zynga India. There was a lot of vision and ability take long term bets on the business.”

Making games for India

While Zynga taught him how to make games, he’d use that knowledge to help make them for Indian audiences at Tiny Mogul Games.

“It was a great place to work because it was a small studio,” he says. “We were doing experimental stuff. We didn’t have massive revenue targets. We focussed on what we can get users engaged with — game developer dream targets.”

This led to two years of experimentation in all kinds of genres leading to 12 games including Shiva: The Time Bender, which was one of the first Indian games to be featured by Google Play globally, and Dadi vs Jellies, which won the Game of the Year award at the Nasscom Game Developer Conference in 2014.

Needless to say, it was one of the better Indian studios around in terms of output and quality of games. One of the titles Ramachandran worked on was Cricket Match — a game that combined cricket and match-three elements.

“The thought process was to look at what would be cool, what we can make Indian, and what would feel Indian,” he says of its development. “Cricket Match was an idea that I had in my head long before I joined Tiny Mogul Games. We had a game jam for some ideas so I tossed it out there and we came up with a cool prototype that we felt was fun which is why we shortlisted it and made it.”

Cricket Match had an intriguing combination that hasn’t been seen since. With good reason sadly, it didn’t resonate with audiences as anticipated. Despite being a game based on his idea he wasn’t blind to its flaws.

“The intersection of audience of match-three games and cricket games is small, I thought it was bigger,” he admits.

While he was deep in the weeds working on Cricket Match, another game at Tiny Mogul was in the works called Dadi vs Jellies. Dadi is the Hindi word for grandmother and the game had you playing as one (grey hair, glasses, sari et al) gunning down cutesy albeit monstrous jellies.

Although Ramachandran claims that he was “not directly involved with the design of the game” outside some “overriding creative direction” he did explain its origins that took inspiration from another match-three hit at the time.

“Jelly Splash was a big thing at the time and the original title was I Hate Jellies,” he says. “Then Huzaifa [Arab, a game designer at Tiny Mogul Games] said ‘why don’t we have an old dadi fighting jellies, that would be cool’ and it stuck.”

The studio’s free flowing creative process would come to halt in due course. Granted its output was phenomenal but the hits were few and far between.

“The first two years was just really try take wild shots at goal which was exhilarating,” he says. “But didn’t make that much business sense really.”

Eventually Tiny Mogul Games was folded into Hike messenger, another Bharti SoftBank-backed venture after amassing five million downloads across its games. To Ramachandran the move made sense.

“Considering that the company merged with Hike, it got focussed to crack games for social on the chat platform,” he says. “Before it was about cracking games for India which I feel was too broad for a studio. It may be okay for a very large company like EA but for a studio like us, cracking India is a huge mandate.”

How games could have saved Hike

This saw Hike getting a games channel along with 20 games. The strategy was not to launch anything wildly inventive, rather it was to make games that were small in scope, easy to understand, and familiar.

These included the likes of solitaire, chess, a few small puzzle games, and a simple endless runner too. It might not seem as glamorous as compared to what Ramachandran worked on prior, but it had its merits.

“We know people liked playing those games, and at this point it was about getting the games channel on Hike to work instead of each individual game at that point,” he says. “It was nothing remarkably original but it was in classic Tiny Mogul Games fashion — highly polished and well-produced.”

Bringing games to Hike was necessary to keep its users engaged amidst poor retention and virality according to reports at the time of its announcement. For a while it seemed to be working.

“We were looking at game channel contribution to Hike DAU [daily active users], what percentage of Hike DAU engaged in games and one of the major things that the channel contributed to Hike was session timing improved dramatically,” he says. “We were also prototyping a lot of interesting social chat games at that point.”

Although it was not to be. Before these social chat games could see the light of day, Hike decided to pull out of gaming.

“It would have been really good if Hike had done better at the time,” he says. “They turned around now, but then it was struggling to get certain basic features right. Rightly so, they deprioritised everything other than the core chat experience.”

Although Hike had shunned gaming then, it appears that some elements of Tiny Mogul’s vision may live on in HikeLand — a virtual hangout feature for the messenger service that’s currently in beta.

Building a game for learning with some help from Disney

With games not being a priority at Hike, Ramachandran wanted to move on. Not before long he found himself at Byju’s, a giant Indian educational tech firm. Considering he had been crafting entertainment experiences for all his career, this move seemed out of the ordinary.

To him though, it seemed like the right place to align his game-making prowess with a desire to improve education.

“I went to Byju’s not as an education guy but as a games guy wondering how can we use this for education,” he says. “I know how to make games, I’m passionate about games. I’ve also got a bee in my bonnet about education. This looks like a great opportunity where I can do that.”

Turns out his past successes with YoVille were right at home at Byju’s that was looking to make more playful offerings targeting the kindergarten to grade three (K3) market.

“I had designed an entire product which was involved like a Zynga game,” he says. “There was an educational aspect to it, allowing you to play, look up videos, and there are decoration, an entire town and a story around it too.”

This ended up being Disney Byju’s Early Learn — a collaboration between the entertainment conglomerate and the edtech company complete with a heavy ad push roping in Bollywood celebrity Shahrukh Khan. Though this was not planned as such.

“In the beginning, we hadn’t designed it with Disney in mind,” he says. “Initially we used our Zynga learnings to make it like a virtual world with learning elements. Disney came on board later on and it morphed into a Disney product.”

Along the way he built Byju’s design team from the ground up, setting up its creative processes as well as “learning about how learning works” as he puts it. After launching Disney Byju’s Early Learn he decided to take a step back.

“Byju’s at that point was very focused on curriculum – English, science, math, that sort of thing,” he says. “I didn’t feel what I wanted to do next was actually going to happen at Byju’s very soon. Because rightly so Byju’s will focus on what matters to their core and their priority will be with what works which is how big companies should work. That doesn’t require me. I’ve already set up the team. It’s working well and has its own momentum.”

Using video games to make education better

What was next for Ramachandran, was trying to answer questions that he had for a very long time.

“Long before I actually went to Byju’s, there were two things I wondered about,” he says. “One: why are we using games so narrowly compared to any other medium? Today if you want to learn something you pick up a book, watch a video on YouTube or sign up for a course on Udemy. Why can’t games be that? Secondly, education itself. I have a fairly rocky relationship with it. I dropped out of college, my son never completed school. We’re guys that don’t fit into the formal education systems. How can we also make education better, more complete and fun for kids who don’t find it appealing or useful?”

And while his work at Byju’s did allow him to scratch that itch, the curriculum-based focus was a far cry from his holistic vision of bringing games and education together. He moved to Chennai and formed Big Fat Phoenix to explore the possibilities of making learning more accessible.

To him, games should eventually sit alongside books and videos as a credible and valid means of learning of any kind.

“To increase and expand the intersection of playing and learning is one of the very core things we’re trying to do,” he says.

Most companies in the space target curriculum-based learning while Big Fat Phoenix wants to address other areas that aren’t as well-represented namely mindset and skill. It’s looking to make games for kids that explore areas like leadership, communication, teamwork, empathy, financial intelligence, balancing a budget, and investing to name a few. Not your typical take at improving in traditional subjects like math, chemistry or geography.

“The education system today is actually focused on information and some skills with math and language,” he says. “A lot of it is just memorising information. I can google a formula and know it but I can’t google how to ride a bike and know how to do it without actually doing it.”

The company believes that information is abundant and will eventually be trivial while honing skills and the right mindset will be valuable. In such an environment, Ramachandran believes games are suited to address this need.

“Games are simulations and for doing something, a simulation is better than a non-simulation,” he says, “We’re looking at how can we use the power of simulations found in games to impact actual learning.”

Right now, games are under-utilised as learning tools, relegated to use for assessment rather than being incorporated into actual learning. It’s something Big Fat Phoenix hopes to change, pointing to the output of developers like Tomorrow Corporation and Blendo Games as examples, though they’re not perfect.

“Games likes Quadrilateral Cowboy and Human Resource Machine is where things like coding, actual teaching, and gameplay is happening as well as logic and algorithmic thinking,” he says. “But broadly, it’s just better assessment.”

The other concern is the quality gap between educational games and those made for entertainment. Ramachandran’s view is that it’s not a question of intent but a question of skill.

“The people making it are very well-intentioned and very good and smart people but they don’t know how to make entertainment, which is a specific skill,” he says. “Today, if you want to make a movie like Avengers, even though you’re a very creative person and your intentions are good, you can’t do it unless you’ve been making movies for 20 years. You’ve got to have the experience, otherwise you can’t do it.”

To him, the answer lies in collaboration between game makers that know how to craft entertainment and educators to make the best products. This isn’t the case at the moment. Though he remains optimistic.

“It’s changing,” he says. “We tried to change that a little at Byju’s. But that’s what is happening. Whereas in a book, you won’t see any difference in the quality of production of a book made for reading a novel versus a book that’s teaching something quality of production will be the same. That’s not happening in games and we want to do that.”

Taking inspiration from Amar Chitra Katha comics

Following his time in advertising and gaming, Big Fat Phoenix is Ramachandran’s third act. With it comes a different set of challenges such as targeting parents or children. The team is drawing from Indian comics, of all places, for inspiration.

“The example I always use is Amar Chitra Katha in the 80s for us when we were growing up,” he says. “Parents would not buy Archie comics for kids because they felt it was bad. Amar Chitra Katha would be bought no problem because the quality was good. It didn’t feel shitty. The books were well-produced. Children felt that they were fun comics to read. Parents saw it as a history lesson or mythology lesson.”

This is a delicate balance and Big Fat Phoenix needs to appeal to both. Though selling parents on games in a market like India may be a tougher than it looks. Ramachandran is betting on the bonding experience of co-operative play to overcome this.

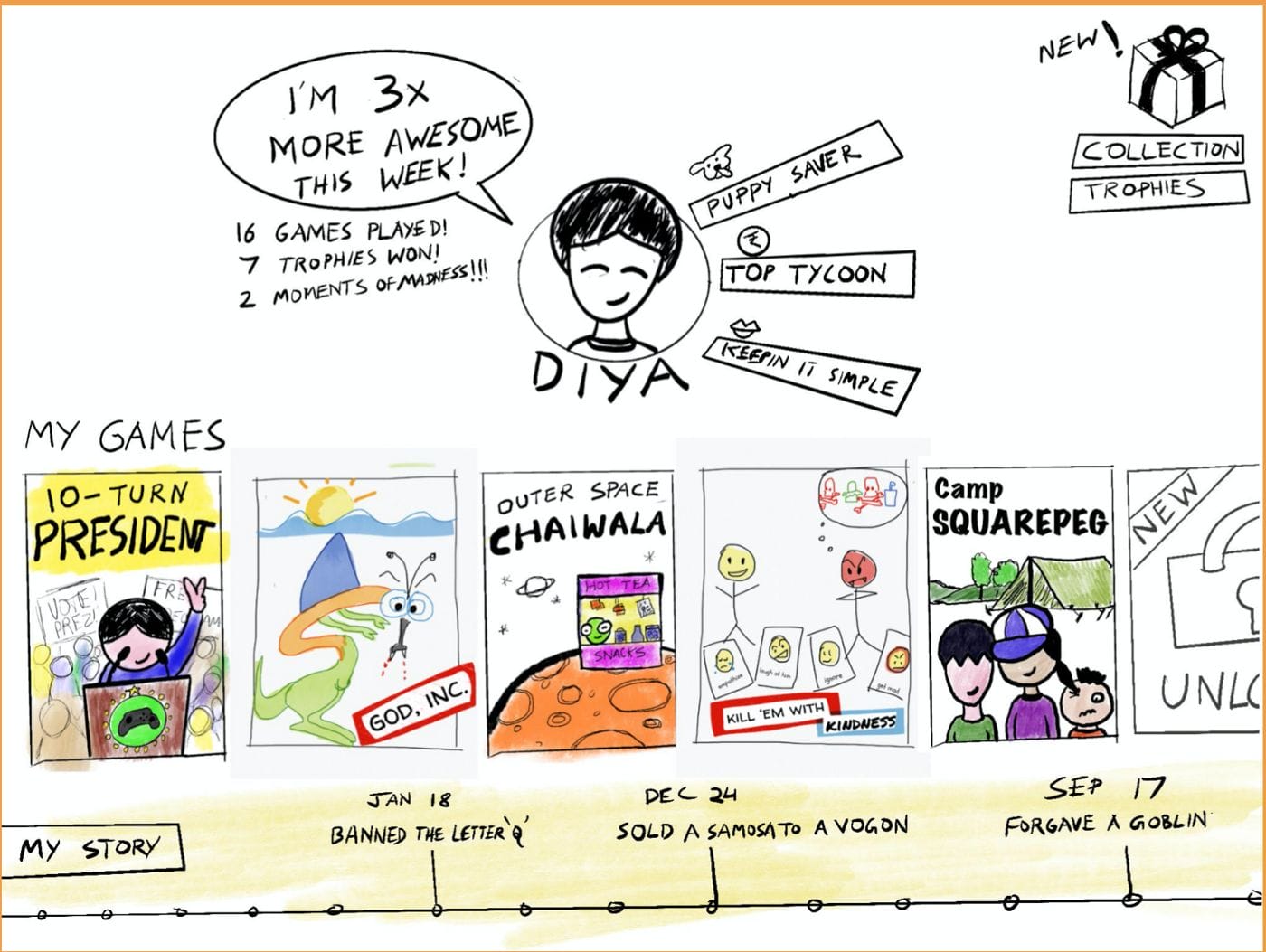

A mockup of one of Big Fat Phoenix’s game concepts.

“We’re actually validating this through some workshops where we bring parents and kids together and we get them to play games together, not our games, just any game,” he says. “We point out the collaboration and learning that happens. I’ve seen parents walk into some of my workshops, saying they hate video games and before walking out ask me to suggest what games they should buy all in a matter of three hours. We’ve done several workshops and continue to do that. So we want to get where we find parents and kids bonding over the same thing because parents and children bond over movies. There is no reason why a large number of them cannot bond over games. And that’s very much part of our strategy.”

Another challenge is its business model. In an age where subscription services are all the rage, he’s refreshingly honest about their prospects.

“I really don’t know,” he says. “The landscape is changing so much and it’s a new category. While a subscription is what we would like to do, we are currently involved in a lot of testing around how exactly we want to go about it and what would work better. Would it be a subscription or would it be just standalone pricing that works better? We just we have to do a lot of experiments to get to that.”

Fundraising during a pandemic

The conversation shifts towards working in the new normal of an ongoing pandemic. It turns out that due to the way Big Fat Phoenix has been structured, there have been few disruptions in day to day operations. The team was remote from its inception with members in multiple cities such as Bengaluru, Chennai, and Kolkata.

“Pre-pandemic we’d travel and meet for two weeks, work remotely for the rest of the month,” he says. “We had a bit of an adjustment phase when it hit but now we’re moving smoothly.”

Perhaps this would be an understatement. With most start-ups are struggling to stay afloat, Big Fat Phoenix managed to raise funds during COVID-19 from WaterBridge Ventures.

“WaterBridge has been really fantastic to work with,” he says before pointing out that his team is the reason why it was possible get a fund raise in the first place. “Even if I die today, they’ll still ship the product and this company will still run. Everybody who’s in this company right now is highly motivated. In fact, they’re all co-owners of the company both legally and in terms of the how much ownership they take over the success of this company.“

A mockup of one of Big Fat Phoenix’s game concepts.

Seeing how Big Fat Phoenix’s success is tied to seeing off the stigma that tends to plague video games, we had to ask what he thought of the current state of the games industry.

“First it was ‘we will make the next great console game out of India’, yeah that’s an immature view,” he says. “Then it was ‘console is nonsense, mobile is the true thing and we will make free-to-play the great revolution’. Again, an immature view. Today there is place in all of these things make what you want. There is opportunity everywhere. Now it’s ‘let’s try and no our games won’t be better than Bethesda’s but we’re going to make good games nevertheless’. This is a mature attitude.”

He points to the likes of PUBG Mobile having a massive impact on the nation, leaving us with this.

“If Modiji says PUBG, then you know that people are talking about it and if Modiji bans PUBG, well the minute a game gets banned, you know that it has arrived,” he says. “If you compare it to 10 years ago, now you are guaranteed to see somebody playing a game on a mobile phone anywhere you go which is phenomenal.”